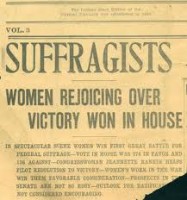

On August 18, 1920, Tennessee passed the proposed 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution by a one-vote margin, becoming the 36th state to ratify the measure and clearing the way for its official adoption eight days later. Incredibly, women’s suffrage in the United States ultimately hinged on an 11th-hour change of heart by a young state legislator with a very powerful mother.

Minutes after Tennessee ratified the 19th Amendment, essentially ending American women’s decades-long quest for the right to vote, a young man with a red rose pinned to his lapel fled to the attic of the state capitol and camped out there until the maddening crowds downstairs dispersed. Some say he crept onto a third-floor ledge to escape an angry mob of anti-suffragist lawmakers threatening to rough him up.

The date was August 18, 1920, and the man was Harry Burn, a 24-year-old representative from East Tennessee who two years earlier had become the youngest member of the state legislature. The red rose signified his opposition to the proposed 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which stated that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” By the summer of 1920, 35 states had ratified the measure, bringing it one vote short of the required 36. In Tennessee, it had sailed through the Senate but stalled in the House of Representatives, prompting thousands of pro- and anti-suffrage activists to descend upon Nashville. If Burn and his colleagues voted in its favor, the 19th Amendment would pass the final hurdle on its way to adoption.

After weeks of intense lobbying and debate within the Tennessee legislature, a motion to table the amendment was defeated with a 48-48 tie. The speaker called the measure to a ratification vote. To the dismay of the many suffragists who had packed into the capitol with their yellow roses, sashes and signs, it seemed certain that the final roll call would maintain the deadlock. But that morning, Harry Burn—who until that time had fallen squarely in the anti-suffrage camp—received a note from his mother, Phoebe Ensminger Burn, known to her family and friends as Miss Febb. In it, she had written, “Hurrah, and vote for suffrage! Don’t keep them in doubt. I notice some of the speeches against. They were bitter. I have been watching to see how you stood, but have not noticed anything yet.” She ended the missive with a rousing endorsement of the great suffragist leader Carrie Chapman Catt, imploring her son to “be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt put the ‘rat’ in ratification.”

Still sporting his red boutonniere but clutching his mother’s letter, Burn said “aye” so quickly that it took his fellow legislators a few moments to register his unexpected response. With that single syllable he extended the vote to the women of America and ended half a century of tireless campaigning by generations of suffragists, including Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, Lucy Burns and, of course, Mrs. Catt. (“To get the word ‘male’ in effect out of the Constitution cost the women of this country 52 years of pauseless campaign,” Catt wrote in her 1923 book, “Woman Suffrage and Politics.”) He also invoked the fury of his red rose-carrying peers while presumably avoiding that of his mother—which may very well have been the more daunting of the two.

The next day, Burn defended his last-minute reversal in a speech to the assembly. For the first time, he publicly expressed his personal support of universal suffrage, declaring, “I believe we had a moral and legal right to ratify.” But he also made no secret of Miss Febb’s influence—and her crucial role in the story of women’s rights in the United States.

“I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow,” he explained, “and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.”

Hi I’m Catherine, founder of Wine Women And Chocolate. Want to become a contributor for Wine, Women & Chocolate? Interested in sharing your unique perspective to a group of supportive, like-minded women?

Hi I’m Catherine, founder of Wine Women And Chocolate. Want to become a contributor for Wine, Women & Chocolate? Interested in sharing your unique perspective to a group of supportive, like-minded women?